Sign up for email updates from Globalisation Café and keep up-to-date on all the work going on at our new, unique website that makes discussion and analysis of globalisation accessible!!

Follow the link here: http://globalisationcafe.com/sign-up/

Sign up for email updates from Globalisation Café and keep up-to-date on all the work going on at our new, unique website that makes discussion and analysis of globalisation accessible!!

Follow the link here: http://globalisationcafe.com/sign-up/

According to US Secretary of State, John Kerry, there is no doubt that the ruling Asad regime isresponsible for what was apparently a horrific gas attack in Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus, on 21 August 2013. Given the so called ‘red line’ that was articulated by President Obama a year ago, and several times since, over the use of chemical weapons, it is unsurprising that the western allies are preparing themselves for some kind of intervention….

According to US Secretary of State, John Kerry, there is no doubt that the ruling Asad regime isresponsible for what was apparently a horrific gas attack in Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus, on 21 August 2013. Given the so called ‘red line’ that was articulated by President Obama a year ago, and several times since, over the use of chemical weapons, it is unsurprising that the western allies are preparing themselves for some kind of intervention….

Read the rest at ThinkIR

I’m honoured to report that one of my previous pieces – The flawed logic of a Sunni vs. Shi‘a ‘civil war’ – for ThinkIR has been translated into Portuguese and featured on the front cover of the latest edition of our Brazilian partner publication ‘O Debatedouro‘.

I’m honoured to report that one of my previous pieces – The flawed logic of a Sunni vs. Shi‘a ‘civil war’ – for ThinkIR has been translated into Portuguese and featured on the front cover of the latest edition of our Brazilian partner publication ‘O Debatedouro‘.

I’m extremely grateful to my friend and colleague Dr Lucas G. Freire – who is also featured in the magazine – for facilitating this exciting partnership!

You can access the edition (PDF Download) here and read the original article in English here.

Given that this blog takes its name from a line of one of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems – made even more famous by the fact it became the title of Edward Said’s famous memoir – it seems only appropriate to mark the passing of five years since Darwish’s death.

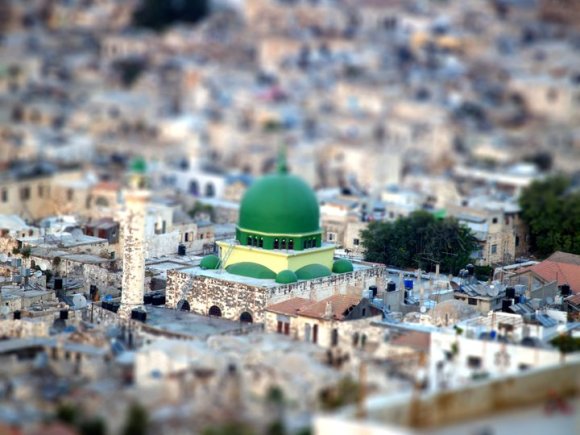

Alongside Said, Darwish must be one of the most famous Palestinians with an appeal that reached out across the Arab world and even managed to break into popular culture in Europe and the US. Born some seven years before the formation of the state of Israel, in al-Birwa in the western Galilee region, Darwish experienced some of the hardships of al-Nakbah (the disaster) himself.

Zionist forces destroyed his village and the family fled to Lebanon. However, unlike the majority of Palestinians who were cleansed from the land in 1948 the Darwish family returned the Acre in 1949, sneaking across the border. The family eventually moved to Deir al-Asad in the Galilee, but were not able to return to the land that they had lost which was now the site of two Israeli settlements.

Darwish earned an education in an Israeli school. But this be no means meant that the family, or indeed any of the Palestinian population in Israel at the time, were treated as equal citizens. In fact Israel maintained a strict policy of keeping its ‘Arab minority’ under military rule until 1986.

Darwish’s mother was illiterate, though he learned to read from his grandfather. According to one obituary, it had been his older brother that first encouraged him to begin writing. Though the young Darwish was exposed to other Arab poetry eventually, though it is interesting to note that initially most of the poetry he would have experienced would have been in Hebrew, either as original texts or translations.

In his youth Darwish endured imprisonment and harassment for his political activism. He became a member of the Israeli communist movement and his poetry appeared in its literary publications. However, in 1970 Darwish moved to Moscow – to attend university for one year – and then to Cairo, he spent the next quarter-century moving between Paris and Beirut, having joined the PLO in 1973 and becoming part of its Executive committee in 1987.

Darwish served in a number of senior positions in the PLO and wrote both Yasir Arafat’s famous speech to the UN in 1974, and the 1988 Palestinian declaration of independence. However, like many other major Palestinian intellectuals, he felt betrayed by the PLO’s embrace of the 1993 Oslo accords and resigned from the organisation.

Darwish as the poet has been called the “Essential Breath of the Palestinian people, the eloquent witness of exile and belonging, exquisitely tuned singer of images that invoke, link, and shine a brilliant light into the world’s whole heart.”

Though I am no poetry expert (!) it easy to see how the major themes in Darwish’s work can be understood prima facie as political commentary. Exile, longing and loss are all notions that are clearly associated with the conditions and experiences endured by millions of Palestinians since 1948. Other poems evoke anger and resistance against injustice. Similarly, gendered tropes that feminise the land of Palestine as something to be longed for, like one’s mother’s bread, are also evident.

But Darwish wasn’t only a political poet. As he explained in an interview in 2001, his concern was only to contribute to Palestinian national identity, but also to the broader project of the development of Arab poetry in general.

—

The fact that Darwish’s poetry was often seen to represent all Palestinians, and embraced particularly enthusiastically by some Western observers and activists – often with an all too superficial grasp on the realities that most Palestinians actually faced and continue to endure – I have found often frustrates many of the Palestinians who I’ve spoken to about him. On many occasions I’ve found that when raising the topic of Darwish with friends and colleagues, it is met with a sigh or rolled eyes.

It is of course possible that it is my understanding of his poetry – which admittedly has mostly been through reading it in translation – that frustrates my interlocutors. On the other hand it might be that it is because Darwish has become such a well-known icon for Palestinian identity that discussions of his work could be taken to be reductive, even insulting. (I can only imagine my reaction if it was repeatedly implied that my own identity could be reduced to the work or actions of a single figure from British history. Sufficed to say I would find it at least annoying; even without necessarily acknowledging the broader power dynamics and my own white privilege!). Either way, at this point my thoughts are merely speculative and thus no reasonably honest analysis can be taken further.

However, what I can say with certainty is that Darwish’s poetry means something to me. It may not be perfect, but I have always found reading it and listening to it – particularly in the author’s own hard, and sometimes rasping, baritone – a rewarding and moving experience. During my studies his work served and an introduction, or re-introduction – for me to several important parts of my life. The most obvious was that his poems helped me see, and come to terms with, a more complex picture of Palestinian identity (though I recognise that this was merely an introduction to a particular set of identities).

It also served as part of my studying Arabic, particularly as I spent many hours working with one of my tutors at Middlebury college on the correct pronunciation for his beautiful “On this earth” which I then got to read in front of a room of other scholars (who were thankfully very generous/forgiving!). But also, it was the experience of enjoying Darwish’s work – as something of a crossover between social science and the ‘real world’ – which also helped trigger a rebirth of my own interest in poetry and literature more generally. I am grateful for that, as it something that has been, sadly, left unattended for too long.

The following youtube video presents one of Darwish’s poems ‘The Dice Player’ with beautiful illustrations. If you don’t click on any of the other links in this post, this is well worth a few moments out of your day.

While Qatar celebrates new leadership the wealthy emirate’s international activism is likely to continue, albeit in a different guise.

Read the article at ThinkIR

GSN Risk Management Reports (special edition 2013)

GSN Risk Management Reports (special edition 2013)

“GSN’s annual New Year assessment of the political and financial factors that impact on the region’s polities and economies finds a marked divide between the Gulf’s high-net worth oil producers and other Middle Eastern populations, who face a more precarious outlook.

GSN’s Risk Management Report 2013 consists of 12 one-page risk management reports on the GCC, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (federation and emirates) and Yemen.

Published alongside a country map, each risk management report includes a political and financial risk grade, factboxes, key economic data, and rounds up noteworthy events and significant trends in a series of short entries on politics and economics.

GSN’s Risk Management Report 2013 is an important reference tool for anyone conducting business in the Gulf region in 2013. It is available as part of a GSN subscription or may be purchased separately.

Price: £75″

Editor: Fiona O’Brien

News Ed: Eleanor Gillespie

Contributors: John Hamilton, Phil Leech

Cartographer: David Burles

Production: Shirley Giles

Editorial Director: Jon Marks

Publications Director: Nick Carn

The flawed logic of a Sunni vs. Shi‘a ‘civil war’

A little article I wrote about the Sunni vs. Shi‘a ‘civil war’ rhetoric that seems to be doing the rounds…

A number of recent documentary films (such as Channel Four’s Aleppo’s Children and PBS’ Syria Undercover) have highlighted the nearly unimaginable horror experienced by those afflicted by the ongoing conflict while the Assad regime fights for its life. But it is not only because of human tragedy that coming to terms with the ‘Arab Spring’ and its fallout, in Syria and elsewhere, is a difficult task. The processes of change that are still in motion are manifold and extraordinarily complex and the nature of emerging political realities remains fluid….

read more at ThinkIR

A little article I wrote about secret courts and the ‘Copenhagen School’

Read on ThinkIR… The challenge of ‘security’ itself

Well, on the 14 December I had my Viva Examination at Exeter where I successfully defended my Ph.D. thesis. My examiners were Dr. Adam Hanieh from SOAS, Professor Tim Niblock and it was chaired by Professor Ian Netton.

Well, on the 14 December I had my Viva Examination at Exeter where I successfully defended my Ph.D. thesis. My examiners were Dr. Adam Hanieh from SOAS, Professor Tim Niblock and it was chaired by Professor Ian Netton.

I’m hoping to get the thesis published and so I’ll hold off on providing too many details… but I do want to say thank you to all those people who’ve helped me getting this done. So here is the acknowledgements page from my thesis. Please note that because I’ve adopted a blanket policy of anonymity towards Palestinian interviewees – a wise precaution in my view – I have not listed the names of individuals here. Thus if your name is not present this should not be taken for ingratitude. Rather, on my next visit, I hope to thank you in person. Indeed for everyone who has aided me in this endeavour I truly am thankful and humbled by your support.

… It should also be noted that one of the people to whom I extend my thanks currently resides in an Israeli prison. He has faced neither criminal charges nor trial. Yet his condition is not unusual – particularly for young Palestinian males – and it serves to remind me of the utterly loathsome and, frankly, ludicrous nature of this occupation. The situation in general, and his condition in particular, are intolerable, untenable, and an affront to basic human dignity.